Can Digital Biomarkers Help Curb Alzheimer's Disease?

Can digital biomarkers be the key to providing a personalized—perhaps even preventative—approach to brain health? What do we know right now? What questions do we need to ask?

Image credits: PopTika via Shutterstock.

Healthy brains—particularly as we age—are crucial to our productivity, creativity, and happiness. That’s why many people fear a Grey (or Silver) Tsunami that impacts economies and healthcare systems around the world. But how do we measure changes in brain health before (currently irreparable) damage has been done? And how do we monitor the effectiveness of potential interventions on a timescale that actually matters to people and their families?

Biomarkers can help answer both of these questions. Traditionally, biomarkers consist of molecules that can be assayed in tissue, blood, or other bodily fluids; an ideal biomarker is cheap and easy to measure in a highly quantitative and reproducible fashion. Biomarkers can be crucial for differentiating among diseases that appear very similar, enabling precision medicine. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, it’s been challenging to identify meaningful biomarkers for brain health that fit these targets.

Broadening our view to digital biomarkers is therefore a promising strategy for personalized—perhaps even preventative—approaches to brain health. Thanks to wearables and the “quantified self” revolution, we can gather an ever larger variety of digital signals that may shed light on an individual’s real-time cognitive function. For Alzheimer’s disease in particular, researchers in labs and companies around the world have explored markers of sleep and physical activity from devices like activity monitors, microphones, smart contact lenses, ingestible sensors, and—of course— smartphone apps.

But out of these 300+ types of digital data, which provide meaningful insight into my cognitive health? That’s the multi-billion dollar question that a coalition of university researchers, Big Pharma, and the nonprofit Digital Medicine Society are looking to answer.

💡 They hope that by focusing today on identifying the most reliable and informative biomarkers, tomorrow we will be empowered to identify participants most suitable for a given clinical trial and to track their responses to a given intervention.

Individual agency is key, because people are different. Some people will want to know about their bodies. Others will not want to know that they are progressing into Alzheimer’s disease—particularly given today’s lack of effective treatments. Here, I think an “opt in” system, with true informed consent, aligns with the three biomedical pillars of justice, doing good, and respect. Today’s healthcare practitioners face an ethical quagmire around these biomarkers … but at the end of the day, everyone can agree that the patient and their families are the people who matter most.

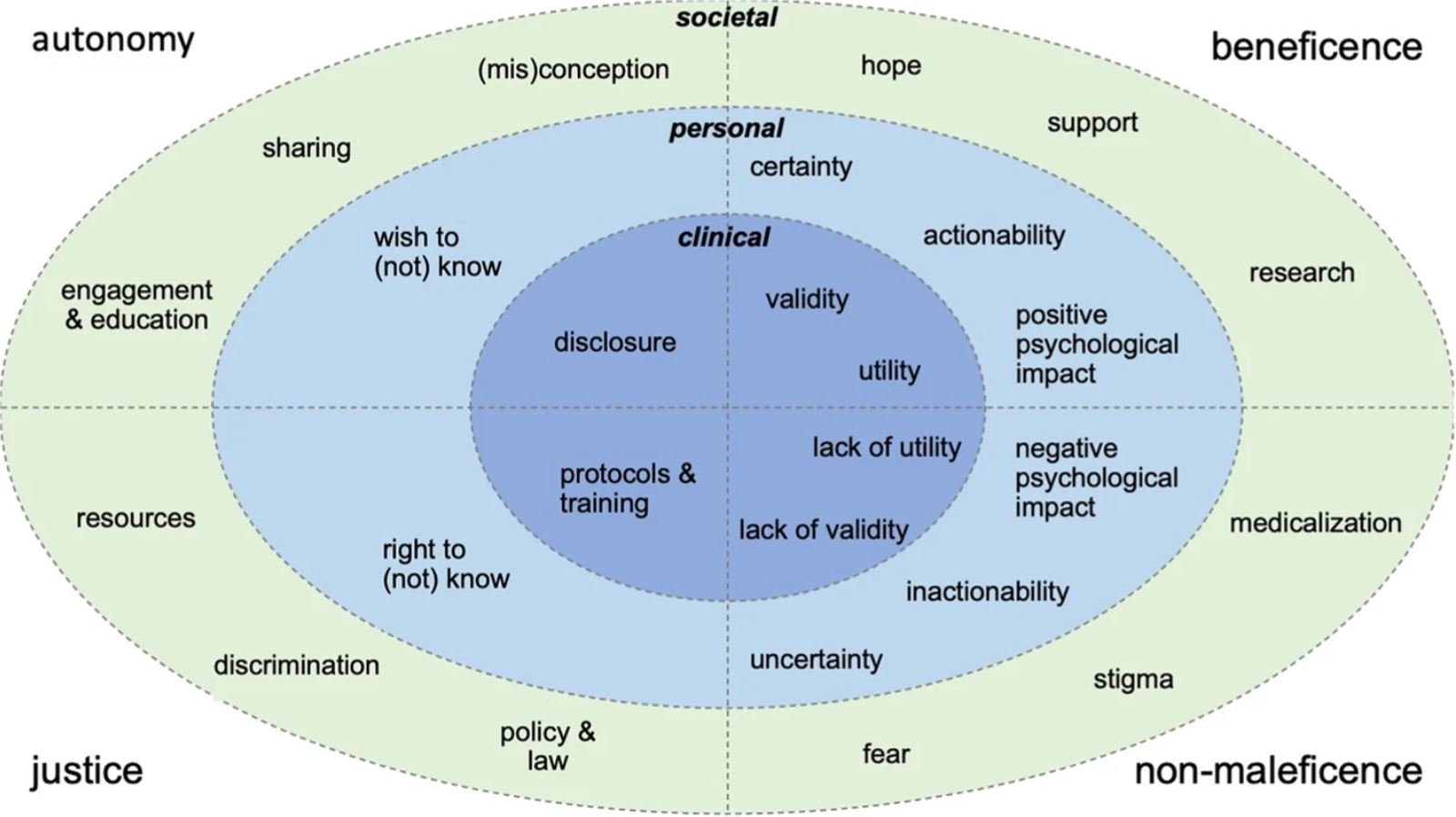

This recent study dived deeply into the literature on these issues in order to visualize the complex interactions among ethics and clinical, personal, and societal concerns. You can think of beneficence as doing good, non-maleficence as avoiding harm, justice as fair and legal resource distribution, and autonomy as enabling the individual to make free and informed decisions.

Image credits: Springer Nature.

You’ve probably guessed that I’m one of those “opt in” people.

I imagine weaving a personalized, “early warning net” for Alzheimer’s disease based on information from the devices scattered around my home.

💡 My smartwatch and smartphone would monitor my gait; my sleep tracker would detect nighttime changes; my smart speaker would be alert to changes in my vocal patterns; my laptop would notice if my typing or app-usage patterns changed. Perhaps my future car would even pinpoint changes in my driving suggestive of cognitive change.

These quantitative data, combined with my biological biomarkers, would help my physician understand both my body and my lived experience. Together, we could craft a personalized set of interventions to support my brain health—and assess whether these interventions actually help me over time.

💡 The overall goal is a future of early diagnosis, early intervention, and frequent measurements that are cheap, convenient, and insightful.

For Alzheimer’s disease alone, achieving this goal would be hugely impactful, for individuals at elevated risk of the disease as well as for the entire aging population around the globe. This goal would also empower new clinical trials that could finally overturn decades of failure to find effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

Today, far too much time is wasted in waiting for visible symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease before a healthcare provider is willing to act. This “sickcare” model means that attention and interventions come far too late. For patients, whose brains have been damaged over years (if not decades) without notice. For families, who have been denied the chance to plan—emotionally and financially—for the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease. And for our society, which would massively benefit from the wisdom contributed by people as they live long and healthy lives.

About Tiffany

Dr. Tiffany Vora speaks, writes, and advises on how to harness technology to build the best possible future(s). She is an expert in biotech, health, & innovation.

For a full list of topics and collaboration opportunities, visit Tiffany’s Work Together webpage.

Get bio-inspiration and future-focused insights straight to your inbox by subscribing to her newsletter, Be Voracious. And be sure to follow Tiffany on LinkedIn, Instagram, Youtube, and X for conversations on building a better future.

Donate = Impact

If this article sparked curiosity, inspired reflection, or made you smile, consider buying Tiffany a cup of coffee!

Your support will:

Spread your positive impact around the world

Empower Tiffany to protect time for impact-focused projects

Support her travel for pro bono events with students & nonprofits

Purchase carbon offsets for her travel

Create a legacy of sustainability with like-minded changemakers!

Join Tiffany on her mission by contributing through her Buy Me a Coffee page.